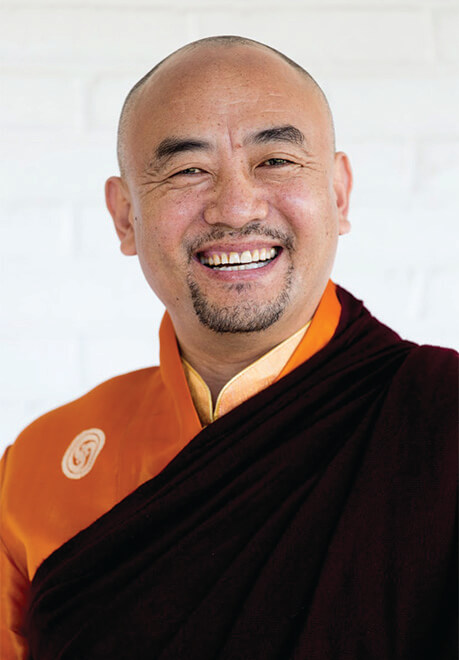

A rare teacher in this modern age. Anyen Rinpoche was raised by a family of yak herders in the high forested mountains of eastern Tibet, a place with almost no evidence of modern life. As a child, he dreamt of foreign-looking people and technological advances. In one particularly vivid dream, he saw "two skies converging." The dream remained a puzzle until Rinpoche was much older, leaving Southeast Asia for the first time. While on a plane flying over the sea towards South Korea, he saw the ocean and atmosphere melding into one on the horizon: two skies converging. It was then that he realized his life was going to follow an unusual course outside his home country of Tibet.

Anyen Rinpoche was raised and educated in a highly traditional manner. When he was three days old, he was recognized as a tulku by the great Dzogchen yogi Chupur Lama. Since it wasn’t possible for him to live in a monastery as a child, Chupur Lama lived with Anyen Rinpoche's family in the same yak-wool tent, transmitting to him all of his early instruction in the Dharma. Chupur Lama also introduced seven-year-old Anyen Rinpoche to his root lama Khenchen Tsara Dharmakirti Rinpoche, after noticing the young boy's intense and profound devotion upon hearing this great master's name mentioned in ordinary conversation.

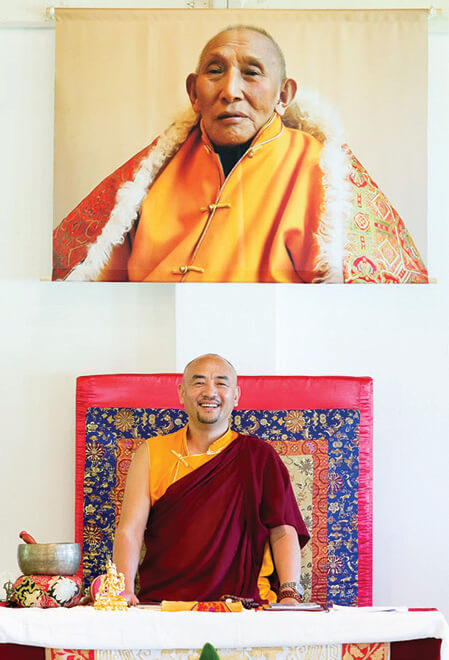

Anyen Rinpoche often speaks of the profound blessings showered upon the practitioner who truly serves their lama with devotion. He himself was such a practitioner, serving Khenchen Tsara Dharmakirti day and night for nearly eighteen years, becoming a master of both practice and study. He not only gained recognition as a great scholar (khenpo), but also became a heart son of his root lama. In doing so, he became the fifth in an unbroken lineage of heart sons who received an uncommonly short and unbroken lineage of the Longchen Nyingthig directly from the renowned Dzogchen master Patrul Rinpoche.

Anyen Rinpoche also received the empowerments, transmissions and upadesha instructions on the channels, wind energies and bindus from the eminent Ngakpa yogi, Tulku Dorlo Rinpoche, a close Dharma friend of Khenchen Tsara Dharmakirti. Additionally, Rinpoche studied Lamrim Chenmo, as well as the Gelugpa style of logic and debate, with Dehor Geshe, another of Khenchen Tsara Dharmakirti's close friends. Since leaving Tibet, he has received empowerments, transmissions and upadesha instructions from many eminent Lamas such as Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche, Yangtang Rinpoche, Khenpo Namdrol Rinpoche, Denpai Wangchuk, and Tulku Dakyong Rolpai Dorje.

Q: Rinpoche, what brought you to the West?

Rinpoche: I think karma brought me to the West. But also, when I think about it, I think it's connected to my previous prayers and aspirations. Since I left Tibet, I have always felt that I must have made strong aspirations to serve the dharma in the modern world, when people’s spiritual practice and compassion is in decline. And also, my dharma friends, such as Onbo and others, said I probably made really strong aspiration prayers to come to the West and to root my Lama's lineage and teachings of the Longchen Nyinthig.

Q: Rinpoche, what was it like being with your root lama?

Rinpoche: The day I decided to follow and commit to studying with my Lama, my ordinary life and way of thinking—everything that I was before, started to fall apart. I had to become more flexible and open and be ready to adapt to any situation. Especially, when I started to study intensively, my day and night, 24 hours, became dharma. What we did was about dharma; what we talked about was dharma. And, of course, what we thought about, the contemplations we engaged in, everything became dharma. In the beginning, of course, it was a little bit challenging. But because of my devotion and irreversible commitment, devotion in the dharma, in him, it transformed me, gradually. Especially, being with my lama, what I feel now is that blessing and that influence is so powerful, so amazing. That ordinary habitual pattern slowly vanishes and all the positive qualities my lama had, started to express in me and in the students. So, eighteen years of every day being with my lama really transformed me.

Also, my lama was really intense and wrathful and it was a challenge to reach his expectations. But I always kept my commitment and encouraged myself to reach that bar. And most of the time, I would say 98%, I can say that I really made my lama happy and fulfilled his expectations and requests. It's something so beyond beyond beyond what modern Buddhists think. It's so important to be with such a master like that, day and night, year by year. That blessing and that transformation is incredible.

Q: What outstanding quality do you feel your lama transmitted to you?

Rinpoche: What I got from my lama is – I used to be really arrogant and not a polite, or a humble person. And I always thought, “I'm really smart and more special than anyone else.” So, my lama really tamed my way of thinking and my arrogance and pride. Whatever good qualities I have are from my lama, but especially, the quality I got through him is that I always think about others first, how others feel. Are others comfortable; are others okay? I think of others, put others before me, and always try to really apply the meaning of the lojong practice. That's what I feel my lama gave me. But, of course, all the good qualities I have are from him.

Q: Rinpoche, what qualities are important in a dharma student?

Rinpoche: I think dharma students should always have this unchanging quality of steadfastness. The most important thing is having that irreversible devotion and being able to keep the connection and develop the connection with the dharma, with the sangha, and with the lama. Keep that commitment and don't be a wishy-washy dharma practitioner. Maybe, not taking a lot of commitments, but whenever making a commitment, really making sure to keep that commitment and improve that commitment. That's something I think is really important and that's also weak in the West. Keeping commitments is a really huge difficulty, or the problem in Western dharma students. But without keeping commitments, it's really hard to improve the dharma practice.

Q: Rinpoche, what is the most difficult part of transmitting authentic dharma in the West?

Rinpoche: I think there's a huge difficulty being a genuinely committed dharma practitioner in the West because it's really new. I think the difficulties are a lack of education and community, such as we have in Tibet. In Tibet, for example, I grew up with dharma. My childhood lama was a dzogchen yogi and my dad is a really good practitioner. And I could see the genuineness of the community, the spiritual practice, the dharma, all around. That influences Tibetan young people, the younger generation. Therefore, they can practice the dharma authentically. We don't yet have enough of this kind of support in the West. Sometimes students feel like they have to choose between dharma and their job or their spouse or other commitments and that can be discouraging. Or maybe their lama lives far away and it is difficult and expensive to travel. They can lose inspiration when they can't easily see the teacher and community. It takes a lot of effort to stay committed when the whole environment is not supporting dharma practice. Therefore, if we are fortunate enough to have a genuine warm and authentic sangha and a genuinely committed spiritual teacher, relying on them, committing to them, supporting them, will help us to really develop genuine, authentic dharma.

Q: What is the most inspiring part of transmitting dharma in the West?

Rinpoche: (laughs) I don't think there are a lot of things inspiring me to teach in the West. (pause) Teaching the authentic dharma in the West is extremely challenging for so many reasons, and there are so many difficulties lamas face here that they don’t face in Tibet. But, when I think about this question carefully – a group of students who are really committed to me are really inspiring me and encouraging me continuously to teach. For example, by buying the dharma center, renovating the dharma center, and sponsoring big statues – all those volunteers and students who are committed to doing a lot of things have touched my heart. Especially, there's a group of students who are pretty committed to my teachings and practice at the Center. For instance, whatever I ask them to do, like making torma or learning how to play instruments, and all of the aspects of ritual practice—whatever I say, they really try to do their best. That is a sign of trust and devotion and that inspires me a lot. It's hard to be inspired to teach Western people. They can be really critical and difficult to teach. Whenever we have programs, in the beginning, just relaxing the students is a huge effort. But at some point, people open up and really understand and connect to the teachings. And at the end of the program, people express the emotions, even crying, and are really grateful and appreciate the teachings. That inspires me to teach.